Baby Ecology book is here! Learn more

Baby Ecology book is here!

- Home

- Baby activities

- How babies learn

How babies learn, how we can help, and why less is more

by Anya Dunham, PhD

Understanding how babies learn can really help you support your little one's innate abilities.

I am sure you know that early childhood is a very important period for brain development. A newborn’s brain is her least developed organ; it will double in the first year and reach 80-90% of its adult size by the time she’s 2 years old.1 But it’s not only brain growth that matters; it’s what happens within it.

In this article, we will explore how babies learn, and what we, parents and caregivers, can do to help. Putting together this information – already there yet largely hidden in disparate pieces in many academic papers – was probably my most favourite part of writing Baby Ecology. There is a really good chance you might find what I am about to show you a bit surprising. It will also run contrary to what baby toy industry would like you to believe. Yet, it’s actually quite intuitive once you see it put together this way.

Let’s take a look.

Why early experiences are important

The part of human brain responsible for intelligence, language, memory, and creativity is called the neocortex. Recently, researchers proved what they had suspected for many years: no neurons are added to the neocortex after birth. In other words, all of the brain cells in the neocortex are formed before a baby is born.2-4 It develops not by adding new cells, but by creating and re-organizing connections within itself.4

Environment matters

The human brain consists of billions of neurons and is wired by approximately 20,000 genes. This may sound like a lot, but a strikingly similar number of genes has been found in a small worm with only 302 neurons. How, then, do human cognitive abilities develop so far beyond those of a worm? Because genes provide only general developmental signals for the human brain: a blueprint, a rough framework; the environment — the experiences we have — is what drives brain construction.5

Childhood is when the majority of brain wiring happens: billions of cells are connected into networks, layers, columns, and functional areas in a process called blooming. Babies’ brains become more highly connected than they will be in adulthood. A typical 2-year-old has at least twice the number of brain connections she will have when she grows up.

That being said, each connection starts out relatively weak. Over time, connections that are used more are strengthened,6,7 while those that are used less are gradually eliminated in a process called pruning. As Dr. Alison Gopnik describes in The Philosophical Baby, babies’ brains look like a map of old Paris, with many winding, interconnected little streets; in contrast, adult brains have fewer but more efficient boulevards and even highways.8

Does this mean we should choose intense enrichment activities for our babies and toddlers so they grow more connections during the blooming phase of brain development? Studies say, no.6,9,10 The number of brain connections appears to be largely under genetic control. Blooming can get disrupted in extreme circumstances like severe malnutrition, toxin exposure, and chronic stress,6 but under normal circumstances experiences do not affect the number of connections. In other words, deprivation disrupts blooming, but enrichment does not enhance it.

Experiences do, however, affect connection strength, ultimately determining which ones stay and which ones get pruned out. What matters is not how much baby is exposed to, but what the events or activities are and how she experiences them.

So what, then, helps babies learn new things and strengthen those brain connections?

This article is based on a chapter in my award-winning book, Baby Ecology. You'll find much more in the book about development, play, feeding, and sleep - all in one place.

How babies learn

1. First, babies make observations

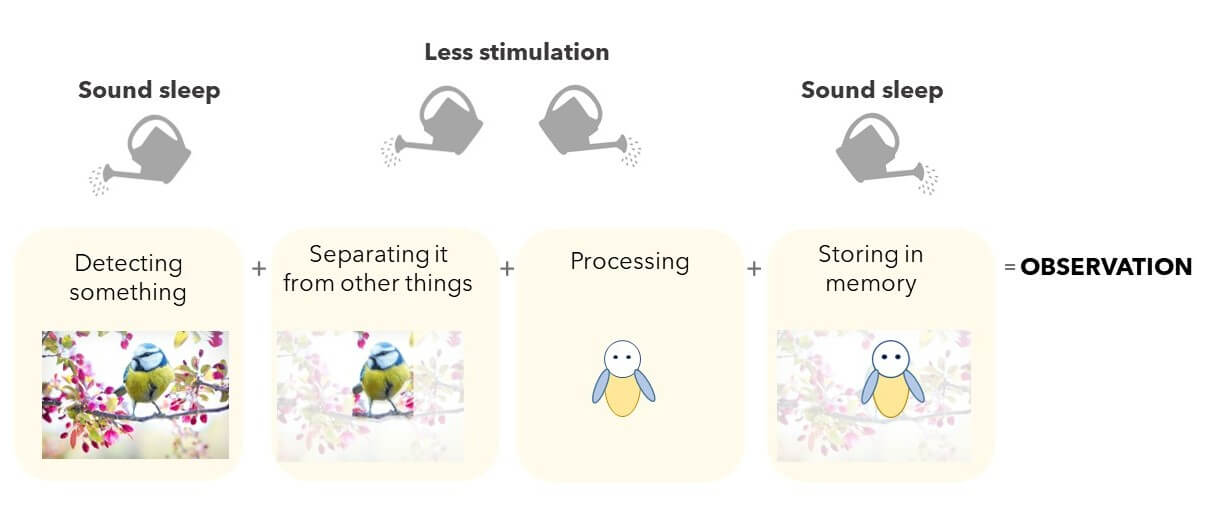

I put this part into diagrams just in case you, like me, are a visual learner.

At the core of any learning is the ability to pay attention and notice new things. To fully notice something, we must detect something new, separate it from everything else, make sense of it, and store it in memory.

Let's say, a baby detected bright colours in a tree. He then visually separated something (a bird), figured out its basic shape, and remembered this observation in some way:

See those little watering cans? I’m using them to show what helps this 4-step process of making an observation:

- Sound sleep helps with the first and last step. It’s easier for a well-rested baby to stay calm and regulated when he’s awake so he can detect new things around him; when he goes to sleep again, his experiences are integrated into memory.11-13 (I like Dr. Avi Sadeh’s analogy here: a baby’s brain is like a librarian who gets a chance to carefully organize books in his care only after the library closes for the day.)

- And for the two steps in the middle, less stimulation is actually better than more. Calmer environments — less background noise, less unnatural movement, less visual clutter — help baby separate new sounds, sensations, and sights from everything else and make sense of them.14

Being rested and not overstimulated is especially important for young babies, but continues to matter through the first year and beyond.

“For an infant ... each new toy, each new movement is stimulation because it is new and has to be learned. When an adult interferes, it is extra stimulation — more than is needed for an infant or small child.” ~ Dr. Emmi Pikler in an interview with Joy Horowitz, June 5, 1981

2. Next, babies combine observations into patterns

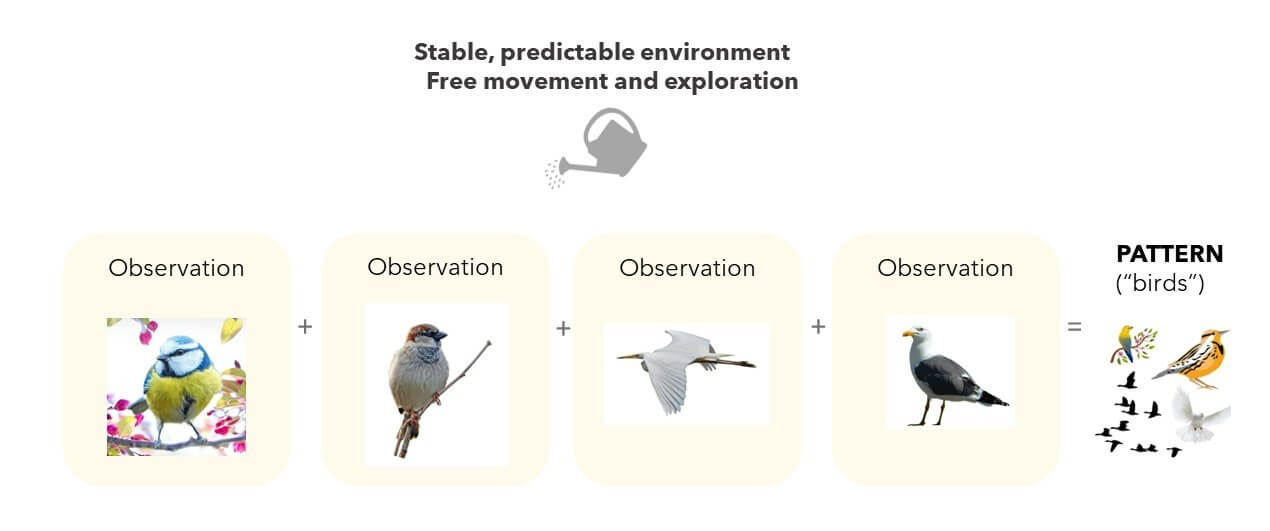

Once our hypothetical baby had a chance to observe birds a few times, he adds up these observations and figures out a pattern:

And this is, essentially, how babies learn. Like scientists, babies place events they have repeatedly observed into categories, and then they use these categories to predict the outcomes of future events. For example, by about 5 months a baby usually learns that when she drops something, it falls down.15 It will take her years to label this as gravity, but she’s discovered a pattern about her physical surroundings. Babies begin understanding that liquids and solids behave differently around 6 months,16 and they gain a sense of object transparency around 8-9 months.17

It’s easier for babies to see patterns when they have opportunities to move around freely and to observe natural events in stable, predictable environments where they see the laws of physics play out again and again. And, of course, babies notice patterns not only in their physical environment, but also in how people around them behave and interact, what events follow each other, and how they feel. For example, a baby may learn that when Mommy says “I’ll be right back” and goes into another room, she’s still nearby and always comes back in a minute; that when food gets dropped, it falls down and he can no longer eat it; and when he looks at a book with Daddy, it will soon be time for bed.

The power of routines

Once a baby figured out a pattern, her brain registers similar objects and events more easily and doesn’t focus on them as much. This is why routines and rituals are so comforting for babies (and adults!): they make the world more predictable and allow babies to save energy for other things that are challenging for them, like emotional regulation.

3. Patterns + surprises = learning

In our example, the next time baby sees a bird, he is not surprised: his brain tags this predicted experience as “usual,” integrates it into existing knowledge, and stops paying attention to it. But when his experience is unusual — for example, he sees a kite! — he cannot easily fit this observation into his existing knowledge. Because of this, his brain pays special attention.18

To recognize these surprising events, babies benefit from interacting with supportive adults and from exploring new objects safely and freely on their own.

- Positive interactions help babies learn new actions and words, especially when adults actively support what babies are interested in. A study showed that when moms routinely play with their babies in a positive but less stimulating way (allowing babies to lead and not tickling or excessively repositioning them), babies show neural activity indicative of stronger early brain development.7

- Exploring new things safely and freely on their own — for example, manipulating simple toys and play objects with different textures, weights, and shapes or simply watching natural events like a ray of sunlight travelling across the carpet — helps babies understand the world around them and develop mastery for more goal-directed play in later years.19

How babies learn: Testing theories

Across studies, babies look for longer17 and show different brain activity when their expectations about the world are not met. For example, in recent experiments 11-month-olds who saw an object defy their expectations paid more attention and explored the object more.20 They even tested theories relevant to the object’s behavior: when they were given a ball they had previously seen rolling off an edge but not falling, they repeatedly dropped it; when they saw a ball seemingly pass through a solid wall, they repeatedly banged it on the floor.20 These babies used the conflict between predicted and observed behavior to gain new knowledge.

Importantly, babies learn about relationships by seeing patterns in how people around them interact. We help our babies see and embody love, respect, and connection. What we do matters.

Creating environments for learning

“Be careful what you teach. It might interfere with what they are learning” ~ Magda Gerber

Bringing it all together, these are the 5 elements that help babies learn:

- Sound sleep

- Not too much stimulation

- Seeing natural events in a stable, predictable environment

- Interacting with supportive, mind-minded adults

- Free exploration

What stands out in this list for you? For me, three things do:

- None of this requires formal teaching or structured activities

- None of this requires purchasing anything

- What is needed is our thought, intention, time, and loving presence

Instead of only focusing on 'educational' toys and experiences, we can put effort into creating environments that support our babies’ innate drive to learn – like good gardens that can support a variety of plants with unique needs and unique strengths (more on this.)

These articles can help you create such environments in your home:

How to create a gated “yes-space” to foster free exploration

Are you practicing mind-mindedness?

The best baby activities may not be what you think

Let me know if you have questions or things to add, via Contact Form, Instagram, or Facebook.

References

References

1. Knickmeyer RC et al (2008) A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. The Journal of Neuroscience 28(47): 12176-12182

2. Bhardwaj RD et al (2006) Neocortical neurogenesis in humans is restricted to development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(33): 12564-12568

3. Rakic P (2006) No more cortical neurons for you. Science 313(5789): 928-929

4. Nowakowski RS (2006) Stable neuron numbers from cradle to grave. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(33): 12219-12220

5. Christakis DA et al (2018) How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: a review of results from observations in humans and experiments in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(40): 9851-9858

6. Dawson G, Ashman S, Carver L (2000) The role of early experience in shaping behavioral and brain development and its implications for social policy. Development and Psychopathology 12: 695-712

7. Bernier A, Calkins SD, Bell MA (2016) Longitudinal associations between the quality of mother-infant interactions and brain development across infancy. Child Development 87(4): 1159-1174

8. Gopnik A (2010) The philosophical baby: what children's minds tell us about truth, love, and the meaning of life. Picador, New York, NY, USA

9. Bruer JT (1998) The brain and child development: time for some critical thinking. Public Health Reports 113(5): 388-397

10. Wastell D, White S (2012) Blinded by neuroscience: social policy, the family and the infant brain. Families, Relationships and Societies 1(3): 397-414

11. Rauchs G et al (2008) Sleep modulates the neural substrates of both spatial and contextual memory consolidation. PLoS One 3(8): e2949

12. Horváth K et al (2018) Memory in 3-month-old infants benefits from a short nap. Developmental Science 21(3): e12587

13. Adair RH, Bauchner H (1993) Sleep problems in childhood. Current Problems in Pediatrics 23(4): 147-170

14. Marshall J (2011) Infant neurosensory development: considerations for infant child care. Early Childhood Education Journal 39(3): 175-181

15. Needham A, Baillargeon R (1993) Intuitions about support in 4.5-month-old infants. Cognition 47(2): 121-148

16. Hespos SJ et al (2016) Five-month-old infants have general knowledge of how nonsolid substances behave and interact. Psychological Science 27(2): 244-256

17. Luo Y, Baillargeon R (2005) When the ordinary seems unexpected: evidence for incremental physical knowledge in young infants. Cognition 95(3): 297-328

18. Cantor P et al (2019) Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: how children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science 24(3): 307-337

19. Messer DJ (2002) Mastery motivation: an introduction to theories and issues. Pp 13-28 in: Mastery motivation in early childhood (ed Messer DJ). Routledge, London, UK

20. Stahl AE, Feigenson L (2015) Observing the unexpected enhances infants’ learning and exploration. Science 348(6230): 91-94

Using hundreds of scientific studies, Baby Ecology connects the dots to help you create the best environment for sleep, feeding, care, and play for your baby.

Warmly,

Anya