Baby Ecology book is here! Learn more

Baby Ecology book is here!

- Home

- Maternal instinct myth

The maternal instinct myth

by Anya Dunham, PhD

The maternal instinct myth is strangely pervasive. No, you won't 'naturally' know what to do – but it's not a bad thing at all.

I am sure you’ve heard of maternal instinct: the idea that women 'naturally' know how to raise children. The maternal instinct myth is strangely pervasive. (Or, perhaps, it's not so strange it persists, given that it's quite often used to explain gender inequality, limit opportunities for women, and justify unbalanced household and parenting loads...)

But is maternal instinct backed by evidence?

What mothering (and parenting in general) is made of – love, responsibility, devotion, sacrifice, joy – is difficult to describe and even more difficult to study. But science can help us answer some of the questions around the maternal instinct myth.

- Will a woman naturally know what to do once her baby arrives? (Short answer: No, it is natural to not know what to do.)

- Should parents trust expert advice or their gut feeling? (Short answer: Both - and, ideally, together.)

Let's take a closer look. I hope you find this knowledge as helpful and empowering as I did 13 years ago when I had my first baby.

The maternal instinct myth

Are women predisposed to knowing how to care for babies – and do men lack such predisposition? Science says, no and no. Maternal instinct as a magical and immediate set of skills and knowledge available to mothers does not exist.

Biologically speaking, an instinct is a behavior that:

- doesn't have to be learned

- shows very little or no variation between members of the species, and

- manifests in a rigid sequence of actions performed in response to a stimulus.

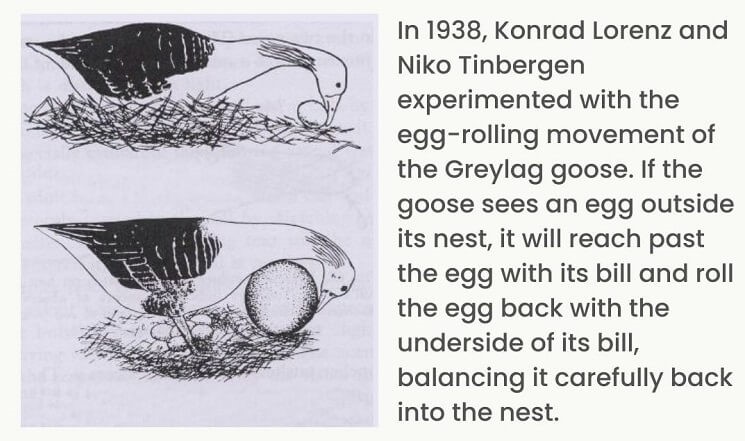

Think, a bear preparing to hibernate or a goose rolling any round object resembling an egg to its nest.

The greylag goose is performing a fixed action pattern that requires no thinking or learning.

That's not what humans do.

Our parenting is a deliberate, thoughtful, and flexible process.

We do, however, have something built in: our caregiving drive, or, as scientists call it, “parental care motivational system”. Neuroscience has shown that seeing babies’ faces and hearing babies cry activates two powerful desires in human adults:

- A desire to nurture which makes us more tender, empathetic, selfless, and caring;

- A desire to protect which makes us extra alert, careful, and risk averse.

Together, these form our caregiving drive. The caregiving drive is universal: it's present regardless of a parent’s gender, sexual orientation, or age. It's activated in both mothers and fathers.1-7 And adults who are not parents show similar brain activation patterns in response to babies.

We are all made to care.

These brain patterns emerge in just 100 milliseconds. This tells us that the caregiving drive is subconscious: it doesn't require rational thinking.6

Universal, biology-based, subconscious caregiving drive makes all of us – mothers, fathers, all committed caregivers – want to care for our babies the best we can. But it does not tell us how. Evolution gave us a neocortex and, with it, neuroplasticity: the amazing ability of our brain's to change and adapt. It gives us incredible cognitive flexibility which, however, comes with a cost: we must learn, and continue learning when our circumstances change.

So, you'll have to figure out the best way to care for your baby yourself, but that's actually good news. Your baby is a unique human, and YOU have the opportunity to get to know them best.

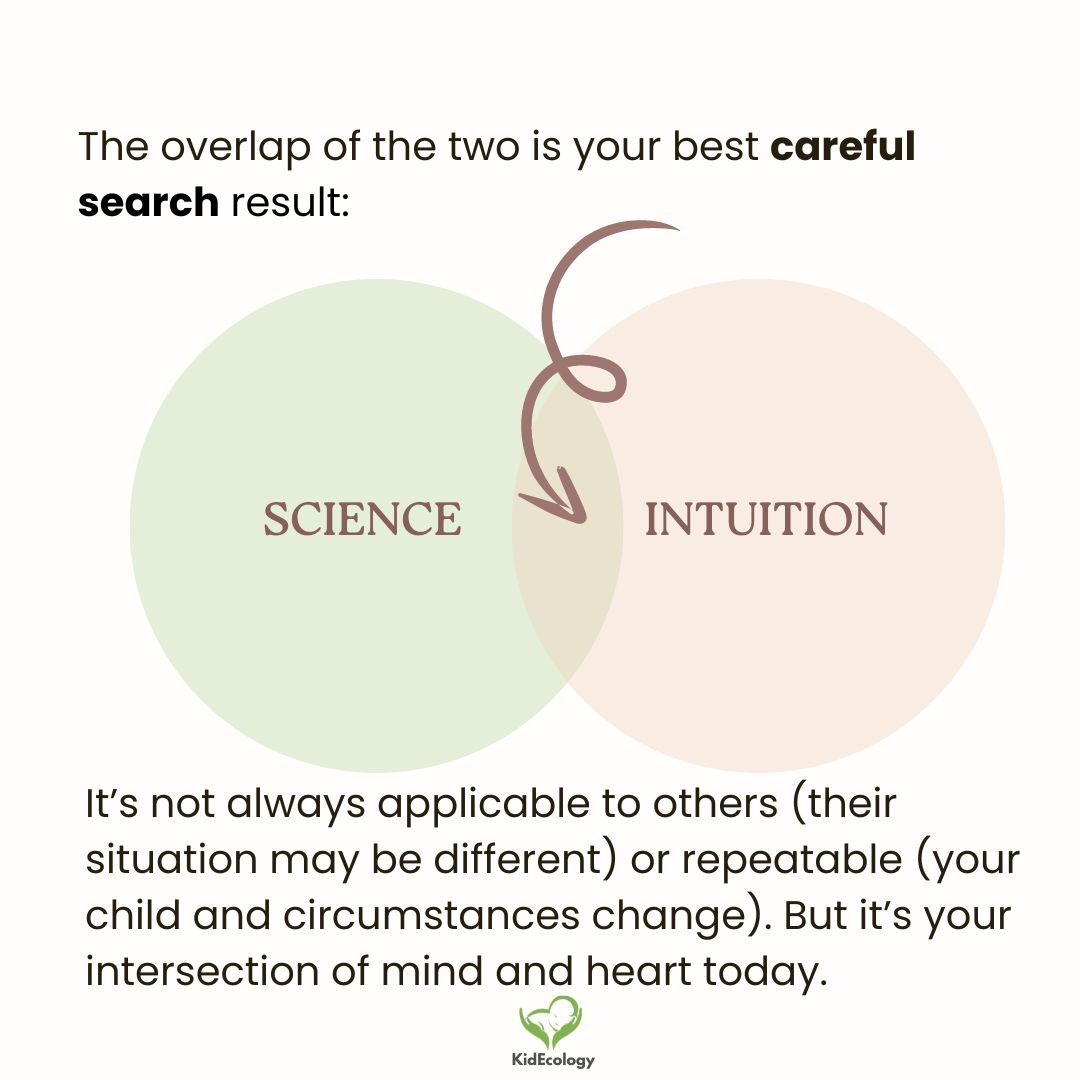

To get to know your baby best, you will need both expert advice and your intuition.

Evidence-based information

Not surprisingly, having access to evidence-based information is known to increase parents' competence and is associated with better child development and health outcomes.8 But surveys show that although most first-time parents want to learn about parenting and child development, they often have a hard time finding clear and trustworthy advice. The volume of information is overwhelming while quality is, at best, inconsistent.9

How can parents find the signal through all the noise?

As a scientist who reads and interprets scientific research daily, I tend to avoid calling online searching "research" so as not to conflate it with the scientific method. I tend to refer to searching for information online as "exploring a topic". But it can be more than that, depending on how we search.

The word "research" comes from old French and means 'to search carefully'. A quick answer from a search engine or AI isn't enough, but if we search carefully and deeply enough, it's usually possible to find a comprehensive and nuanced picture.

Most parents don't have the time or expertise to sift through dozens of scientific papers, but reading only one or two can lead to confusion and misinformation on the topic. As you look for answers to parenting-related questions, prioritize:

- Overviews or position statements from the World Health Organization, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), or an equivalent organization in your country

- Recently published review papers in reputable scientific journals

- Last but not least, your and your baby's health care providers' professional advice

Your intuition

If maternal instinct is a myth, why do so many parents and caregivers have such a strong sense of just knowing when something is wrong (or right) with their children? This “sixth sense” or “gut feeling” – our intuition – indeed exists. But it does not magically switch on the moment we become parents.

In contrast with conscious and deliberate evidence-based knowledge, intuition is subconscious and automatic: it allows us to know something without analyzing or weighing the facts. It’s a way of knowing without being able to explain how we know.

But intuition is still a very real form of knowledge, because, as it turns out, it has to do with the way our brains store, process, and retrieve information.10,11 When you have that “gut feeling”, your brain subconsciously combines information drawn from your past experiences and stored in your memory.12

So, intuition is the synthesis of experiences we carry within us. But where do these experiences come from? Well, it could be:

- Careful observation;

- Culture; or

- Biases and fads.

These three sources are not equally reliable. Because of this, intuition can be amazingly accurate. It can also be very wrong.13

~ Careful observation

The first source of parenting intuition is our children themselves. We develop intuition as we spend time with them and get to know them better than anyone else. For example, intuitive parents speak directly to their baby, adjust distances based on how far babies can see, and fine-tune what they do sensing their baby’s need for stimulation or rest.14

Careful observation will help you get to know your baby and understand her needs – and doing so will help your baby’s natural development unfold. Seemingly small things you notice will accumulate over time to form your special intuitive knowledge of your baby.

~ Culture

Intuition can also stem from cultural beliefs. Cultures differ in routines and rituals, sleep arrangements, traditional foods, and many other aspects of daily life. Parenting within culture can create experiences and environments that are positive, consistent, predictable, and similar to what children are likely to encounter outside their family as they grow. However, acting upon intuitions that stem from cultural beliefs blindly - without checking them against evidence-based knowledge – can lead parents astray.

For example, a cultural belief that babies are born “blank slates” could lead parents to missing their baby’s unique abilities and temperament, expose baby to overstimulation, and impact secure attachment. (When in fact, science shows babies are born very tuned in.)

~ Biases and fads

Finally, what we consider intuition may also be what Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman in Nurtureshock call “a hodgepodge of wishful thinking, moralistic biases, contagious fads, personal history, and old (disproven) psychology”. There are also parenting fads, "must-do" messages we receive from parenting influencers. When we carry media messages or peer pressure in our memories, we might subconsciously use them for what we think is intuitive decision-making. Such intuitions are usually wrong. (In fact, the existence of the maternal instinct myth itself might be, at least in part, perpetuated by biased thinking "women are naturally better at parenting than men".)

Combining evidence-based information and intuition

Happily, research suggests that our brains are able to combine intuitive and evidence-based knowledge even when we are not fully aware of where our intuition is coming from.15 This is important. It means that evidence-based knowledge can help you hear your true intuition.

Not knowing is a good thing

I remember a friend saying: “I am a mom, and I should know what I am doing. I should be naturally good at this, but I don’t think I am...”

The maternal instinct myth is so common and persistent. But what is natural and perfectly okay – in fact, more than okay – is to not know what to do when you become a parent. Whether you are a new mom or a new dad, a biological parent or an adoptive parent, you will not naturally know what to do.

The maternal instinct myth is pervasive. Expecting this non-existing instinct to kick in can create anxiety, stress, and a sense of failure. Hear me discuss this on The Science of Motherhood Podcast with Dr. Renee White.

Look for evidence-based information: advice from trusted health care practitioners and scientists. Consider this advice deliberately and carefully before making decisions, and it will help you filter out irrelevant cultural messages, biases, and fads you could have mistaken for intuition. Then, you are free to use truly intuitive knowledge – your unique knowledge that comes from carefully observing your baby – wisely.

If you have a partner, share this article with them. Learning to parent as a team is one of 3 ways to strengthen your relationship after becoming parents. Let's help make the maternal instinct myth a thing of the past!

References

References

1. Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Rigo P, Esposito G, Swain JE, Suwalsky JTD, et al. (2017) Neurobiology of culturally common maternal responses to infant cry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(45):E9465-E73

2. Swain JE, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Strathearn L. (2007) Brain basis of early parent–infant interactions: psychology, physiology, and in vivo functional neuroimaging studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48(3‐4):262-87

3. Swain JE, Kim P, Spicer J, Ho S, Dayton CJ, Elmadih A, et al. (2014) Approaching the biology of human parental attachment: Brain imaging, oxytocin and coordinated assessments of mothers and fathers. Brain Research 1580:78-101

4. Gustafsson E, Levréro F, Reby D, Mathevon N. (2013) Fathers are just as good as mothers at recognizing the cries of their baby. Nature Communications 4(1):1-6

5. Abraham E, Hendler T, Shapira-Lichter I, Kanat-Maymon Y, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. (2014) Father's brain is sensitive to childcare experiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(27):9792-7

6. Young KS, Parsons CE, Jegindoe Elmholdt E-M, Woolrich MW, van Hartevelt TJ, Stevner AB, et al. (2016) Evidence for a caregiving instinct: rapid differentiation of infant from adult vocalizations using magnetoencephalography. Cerebral Cortex 26(3):1309-21

7. Schaller M. (2018) The parental care motivational system and why it matters (for everyone). Current Directions in Psychological Science 27(5):295-301

8. Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Haynes OM, Hahn C-S, Park Y. (2010) Parenting knowledge: Experiential and sociodemographic factors in European American mothers of young children. Developmental psychology 46(6):1677

9. Zero to Three and the Besos Family Foundation Foundation (2016) Tuning In: Parents of Young Children Speak Up About What They Think, Know and Need: https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/series/tuning-in-parents-of-young-children-tell-us-what-they-think-know-and-need

10. Papoušek H, Papoušek M. (2002) Intuitive parenting. P. 183-203 in M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Biology and ecology of parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

11. Hodgkinson GP, Langan‐Fox J, Sadler‐Smith E. (2008) Intuition: A fundamental bridging construct in the behavioural sciences. British Journal of Psychology 99(1):1-27

12. Baylor AL. (1997) A three-component conception of intuition: Immediacy, sensing relationships, and reason. New ideas in psychology 15(2):185-94

13. Myers DG, Myers DG. (2002) Intuition: Its powers and perils: Yale University Press.

14. Koester LS, Lahti-Harper E. (2010) Mother-infant hearing status and intuitive parenting behaviors during the first 18 months. American Annals of the Deaf 155(1):5-18

15. Lufityanto G, Donkin C, Pearson J. (2016) Measuring intuition: nonconscious emotional information boosts decision accuracy and confidence. Psychological science 27(5):622-34

Using hundreds of scientific studies, Baby Ecology connects the dots to help you create the best environment for sleep, feeding, care, and play for your baby.

Warmly,

Anya