Baby Ecology book is here! Learn more

Baby Ecology book is here!

- Home

- Baby activities

- Screen time for baby

Screen time for baby: the 'why' behind the recommendations

by Anya Dunham, PhD

Is screen time for baby 'bad'? Are there any positives? Let’s look at scientific studies to find out WHY screentime isn't recommended in the early months and years.

(This article is based on a chapter in my award winning book, Baby Ecology.)

I'm sure you are familiar with the 'no screen time for baby' recommendation. And I'm sure you've also seen many questions and counter-arguments in online communities, along the lines of "but this content is educational", or "what about those slower-paced shows?", or "it hasn't been studied enough".

Screen time can be a loaded and sensitive topic. And it can be quite confusing.

In this article, I'll show you why screentime isn't beneficial at all in the early months and years, and why it can, in fact, be harmful. We might learn more about it, but we do already know enough. My hope is that knowing this WHY will help you see through the noise and make decisions that work best for your family.

Screen time for baby

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended no television viewing for children younger than 2 years old in 1999. This recommendation was reiterated and extended to mobile technology in 2011. In 2016, the AAP issued an update recommending no screen time except for video-chatting for children under 18 months, and carefully chosen high-quality programming, watched with a parent, beyond 18 months. In 2019 the World Health Organization recommended no screen time for children under 2 years old.

First, a tiny bit of history

In the 1970s, most children began watching TV regularly around 4 years old.1 Then, in the 1990s, baby-directed videos and television programs like the Baby Einstein series and Teletubbies began to appear. Most were marketed as educational tools to promote brain development and cognitive skills. And by the early 2000s, the average age children began watching television became 4 months old. At 3 months, 40% of babies were already regular viewers; by 2 years, almost all babies were.1 In 2005, every fifth child under 2 years old in the United States had a TV set in their bedroom.2

Six-month-old Jax is watching a television show. He is sitting very still and appears to be watching the screen intently.

Jax can hear the sounds and see what’s happening on screen almost as well as his big brother and his parents. He can recognize simple shapes. But all he’s experiencing is a stream of flashing lights and colors, with no apparent connection to each other, to the sounds he hears, or to the people and objects in his life. Jax will not begin comprehending the show’s content or even sequences of events until he is at least 18 months old.3,4

In a large survey completed back in 2006, parents shared their reasons for letting babies and young toddlers watch television, DVDs, or videos. Most believed the programs were educational and good for their child’s developing brain, and that viewing was enjoyable and relaxing.1 Most considered screen time for baby a positive.

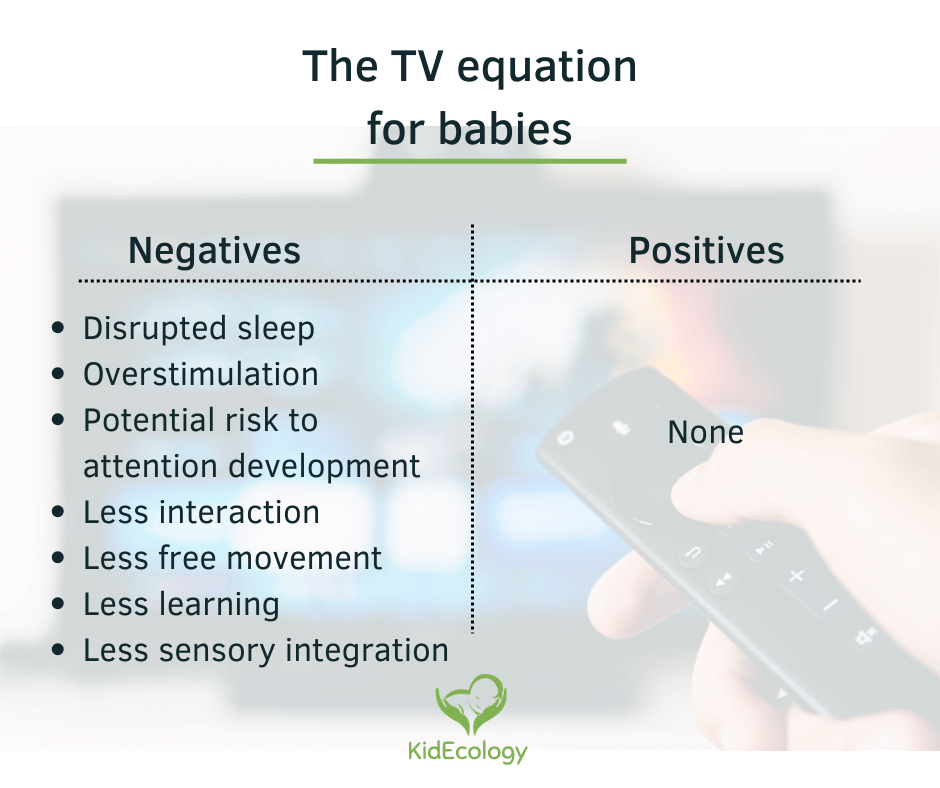

Unfortunately, it's not. Researchers have been actively looking into the effects of television and video exposure on babies and young children since the early 1990s, and at this point science has given us some solid answers. Let’s take a look at the TV equation.

Screen time for baby: The negatives

There are three main negatives that are correlated with — and may be caused by — watching TV:

- Disrupted sleep. Babies who watch TV tend to have less regular sleep5 and generally sleep less.6 Although the sleep loss is usually small, from a few minutes to half an hour per day, researchers warn that it can add up over time and create patterns that lead to a significant sleep deficit as the child grows.6 Television viewing disrupts sleep in at least two ways. The blue light emitted from screens disrupts the production of melatonin, a hormone essential for healthy sleep.7 In addition, viewing screens in itself is known to stimulate alertness.2

- Increased risk of myopia. A recent large study of 26,433 preschoolers in China found that screen exposure in early life is associated with the occurrence of preschool myopia (nearsightedness), with the strongest association found in the group of children initially exposed to electronic screens before they turned 1 year old.16

- Overstimulation — and its effects on baby's developing attention. Rapid changes trigger babies’ orienting response: a reflex that fixes their attention on new sights and sounds. This response is good and necessary; in fact, it’s the cornerstone of babies’ learning. However, rapid-fire changes on screens are dizzying compared to the pace of real life — the pace the human brain spent millennia adapting to. Flashing lights and quick changes on screen overstimulate baby’s developing brain3 as the part responsible for orienting response fires away (“Alert! Change!”).

This is why baby Jax in our example above is sitting very still and watching intently. His developing brain is trying to figure out what’s happening (“Is this threatening? Is this important?”), but doesn’t get the chance to process any input.

Watching television is not relaxing for babies at all. In fact, it’s likely stressful and exhausting!

As babies grow, their attention gradually develops from orienting response toward executive attention, otherwise known as focus: they begin selecting specific information from sensory input.8 Researchers believe that excessive television viewing may disrupt this natural process of attention development.

The pacing of television shows, even those designed for babies, is extremely rapid compared to real life. Sensory overstimulation may condition children’s developing brains to expect this level of stimulation and intensity in everyday lives.

Some studies have found an association between very early exposure to television and attention problems. For example, children who watched 2 hours of television a day before age three had a 20% greater chance of attention problems in elementary school, compared to those who did not watch television as babies and toddlers; watching faster-paced shows was more strongly associated with subsequent attention problems.9

It is important to note that these studies found a correlation between screen time for baby and attention — not causation. In other words, we cannot confidently conclude that screen time, or screen time alone, is the reason for later attention problems. To arrive at robust conclusions, one would need to conduct experiments that are not possible for ethical reasons: thankfully, no researcher would purposefully expose young children to what’s likely to be detrimental sensory overstimulation to see whether it would cause hyperactivity or cognitive impairment. So all studies on television viewing and attention in children have been — and likely will be — observational rather than experimental.

Recently, however, an experiment was conducted on mice. Some young mice received excessive sensory stimulation: bright lights and sounds for 6 hours per day for 6 weeks (simulating a television-heavy household). These mice showed signs of impaired learning, impaired memory, increased risk-taking, and hyperactivity which researchers described as “ADHD-like.”10 We cannot directly extrapolate these findings to young humans, of course, but they are important to consider as we may never have much more definitive answers from science on this topic.

There are several other negatives. These are not directly caused by television, but stem from what babies are not doing or getting during the time they are immersed in screens.

Screen time for baby leads to:

- Less interaction: Time babies spend watching screens is not spent interacting with caring adults or other children.

- Less free movement: During screen time babies are physically passive, often strapped in infant seats or other “baby containers”.

- Less learning: Babies begin to grasp the laws of physics by recognizing patterns in daily life from a very early age. The television world, however, does not have the same laws. In real life, a ball moving to the right will continue to move to the right until it stops. But a ball on screen moving to the right may disappear from view, only to reappear on the left to continue the rightward motion in an edited action sequence.4 Watching screens does not help babies learn about the world around them. (More on the 'video deficit', or why babies don't learn much from screens.)

- Less sensory integration: Sensory input coming from the screen is not as coordinated as real life.11 For example, watching a flower on screen does not allow a baby to experience the full sensations of touching and smelling a real flower. Learning is harder without a complete picture. And sensitive windows for sensory integration occur quite early: pruning in the sensory cortex begins as early as 8 months.12 Recently, researchers found that babies who watched TV at 12 months were more likely to have sensory sensitivities and an overall different sensory processing profile compared to babies who didn't watch TV.13

These are, essentially, lost opportunities. Are they significant? They can be, depending on how much time babies spend watching. According to a large survey, 3-month-olds on average watch about an hour each day.1 This might not seem like much. But babies of this age sleep for 16 or more hours per day and spend another 3 or so hours feeding and being changed and dressed. So screen time takes up almost a quarter of their awake time. Being in a screen-free environment gives babies more opportunities for connecting, building strength, exploring, and learning.

What about TV being on in the background? Background TV still affects babies even when they’re not actively watching (more on that here).

Screen time for baby: The positives

What about the educational benefits claimed by the producers? The problem is, even if a show’s content can be considered educational, babies are not developmentally ready to understand it. Watching screens is a demanding cognitive activity, one that requires special forms of attention, perception, and comprehension.4 Babies develop these skills through exploring, connecting, and playing in the real world, not by watching screens.

Some programs claim to teach babies languages. The Baby Einstein series was inspired by the finding that young babies are sensitive to phonetic contrasts of any language, but at around 6 to 9 months they begin to gradually lose this generalist sensitivity: their brains focus on the language they hear most. So Baby Einstein videos exposed babies to the sounds of many languages and were supposed to help them remain sensitive to many phonetic contrasts, to facilitate later language learning.

However, there is a problem. Videos like Baby Einstein don’t actually work.

A number of studies have now shown that babies learn much better from real people and real-life events than video — and that this “video deficit” phenomenon holds true until the child is 2 to 3 years old, and likely beyond.3,4,14 In 2009, Disney offered refunds on Baby Einstein videos because its claims of learning benefits were unsupported. That being said, a plethora of “educational” videos and apps for babies have been developed since.

Some media content producers claim that their goal is to promote child-parent interaction. However, studies show that most parents do not watch television with their babies or toddlers.1 (Understandably so – they are probably trying to catch a break.) And even when babies and their parents are watching together, they are probably interacting less than if they played with blocks, looked at a book, or just went about daily activities together.

Overall, statements by television and video producers that their products are beneficial for babies are not supported by evidence. Most or all television and video content should not be marketed as educational or even developmentally appropriate for babies and toddlers. Yet there still appears to be a lack of regulation regarding such marketing claims.11

What about interactive technology?

But what about devices like tablets and smartphones? Do they create better, interactive screen time for baby?

Many babies use their parents’ devices and may even have their own, made specifically for young children. The effects of mobile technology are not yet well studied, but the list of negatives described above very likely applies just the same. Babies under 1 are exposed to the same type of content they would have been watching on television, but now from a mobile electronic device.

Moreover, some of the negatives may be amplified. Electronic devices are portable; many attach to car seats and strollers, lending themselves as “electronic babysitters” to keep babies occupied during daily routines. This has the potential to increase babies’ screen time in a very real but not easily noticeable way. In addition, mobile screens are smaller and positioned much closer to babies than television screens. This could have an even larger impact on babies’ sleep because the blue light is stronger at close distances. Looking at screens up close for considerable amounts of time may also pose risks for babies’ developing vision.11 It may re-wire their visual systems toward up-close central fixation and lead to under-developed peripheral and distance vision.15 The degree of these risks is currently unknown.

*

Q: I want my baby to be screen-free. But how do I ever catch a break?

Consider creating an enclosed, 100% safe play area (or “yes space”, as Janet Lansbury calls it) where your baby can play, move, and explore freely, with you or on their own. Read more about this concept and how we created ours here.

Q: My baby won’t eat unless the tablet is on. What can I do?

Begin shifting towards baby-led feeding, where you set up a nurturing feeding environment and provide nutritious foods at regular times and your baby decides how much of each food to eat and whether to eat it at all – without coercion or distractions. Find out more here.

Q: My baby enjoys pressing buttons and swiping a touchscreen on my phone. Isn’t this good for her fine motor skills and for learning how devices work?

Sure, screens (and electronic toys) can teach your baby how to press and swipe. But if you think about it, these tasks are very simple, can be learned any time in life, and are rather meaningless on their own. To use electronic devices in a meaningful way, one must first understand how the real world works outside of the screen. For example, as your baby plays with a toy drum or a spoon and a plastic container, she will learn that banging objects together makes a sound. She will also learn that the sound varies depending on how soft the object is and how hard she hits it, and that hitting water makes a splash; she will be using all her senses. If she’s curious about sounds, she’ll keep experimenting, which will advance her strength, fine motor skills, and sensory integration, and give her a sense of mastery. She won’t learn any of that from simply pressing a button or swiping on a smartphone to produce a sound. (More on light up toys and screens comparison.)

Summary

Is screen time for baby 'bad'? Science does not conclusively tell us watching screens directly causes problems, but it does strongly suggest a number of negatives watching screens is associated with.

And it does not show any positives at all.

Technology changes rapidly, but the biology of early childhood development remains the same. Of the 5 things babies need most for brain development – sound sleep, avoiding overstimulation, predictable environment, interactions with supportive adults, and free exploration – screens provide none.

In my award-winning book, Baby Ecology you'll find a comprehensive chapter on babies and screens — along with many ideas for creating the best conditions for your baby's learning and development.

References

References

1. Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA, Meltzoff AN (2007) Television and DVD/video viewing in children younger than 2 years. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 161(5): 473-479

2. Vandewater EA et al (2007) Digital childhood: electronic media and technology use among infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Pediatrics 119(5): e1006-e1015

3. Anderson DR, Pempek TA (2005) Television and very young children. American Behavioral Scientist 48(5): 505-522

4. Anderson DR, Hanson KG (2010) From blooming, buzzing confusion to media literacy: the early development of television viewing. Developmental Review 30(2): 239-255

5. Thompson DA, Christakis DA (2005) The association between television viewing and irregular sleep schedules among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics 116(4): 851-856

6. Cespedes EM et al (2014) Television viewing, bedroom television, and sleep duration from infancy to mid-childhood. Pediatrics 133(5): e1163-e1171

7. Dawson D, Encel N (1993) Melatonin and sleep in humans. Journal of Pineal Research 15(1): 1-12

8. Posner MI, Rothbart MK, Voelker P (2016) Developing brain networks of attention. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 28(6): 720-724

9. Christakis DA et al (2004) Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children. Pediatrics 113(4): 708-713

10. Christakis DA et al (2018) How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: a review of results from observations in humans and experiments in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(40): 9851-9858

11. Haughton C, Aiken M, Cheevers C (2015) Cyber babies: the impact of emerging technology on the developing infant. Psychology 5(9): 504-518

12. Tierney AL, Nelson CA III (2009) Brain development and the role of experience in the early years. Zero Three 30(2): 9-13

13. Heffler KF et al. (2024) Early-life digital media experiences and development of atypical sensory processing. JAMA Pediatricts doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.5923

14. Kuhl PK, Tsao F-M, Liu H-M (2003) Foreign-language experience in infancy: effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100(15): 9096-9101

15. Doige N (2007) The brain that changes itself. Viking, New York, NY, USA

16. Yang GY, Huang LH, Schmid KL, Li CG, Chen JY, He GH, Liu L, Ruan ZL, Chen WQ (2020) Associations between screen exposure in early life and myopia amongst Chinese preschoolers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(3): 1056

Using hundreds of scientific studies, Baby Ecology connects the dots to help you create the best environment for sleep, feeding, care, and play for your baby.

Warmly,

Anya